Introduction:

At the outbreak of WWII, my grandfather Michel Van de Sijpe , born on May 8, 1926, lived at Gentse Steenweg in Zottegem

On May 14, 1940, a few days after his fourteenth birthday, he witnessed the crash of an English fighter into the fields nearby the Leenhoutstraat around 200 metres from his home.

His personal memories of the crash and the days following his birthday were engraved in his memory which helped the investigation.

As a child, I heard this story several times. What started with a story, became an intense study for me.

I was eager to find out what exactly happened that day.

In the following report, you will find the results of a tedious and intensive search of many years.

The research:

For years, I have been collecting information during the visits to my grandfather. What started with a few sentences in my notebook, became very detailed over time. My research started with the little information and details I had.

-It was on May 14 at noon.

-It was an English single-engine aircraft and the pilot died the following day in the local hospital from his burns.

Through a cultural organisation of Zottegem, I got my hands on war diary excerpts written by Omer Coessens, a resident of Zottegem. Therein, an English pilot was mentioned who was taken to the local hospital for nursing. Unfortunately, the original diary got lost so I was unable to gain more information.

I brought a visit to the hospital and after reporting about my research, I was given access to the hospitals’ archives from the war years.

As somehow expected, I did not find more information that could boost my research. Even the relatives of the doctors on duty at that time in 1940, were ignorant about this story.

I decided to focus on the crash site itself. Google Earth, Geopunt and a subscription to the online archive of WW2 aerial photographs in Scotland have been of an indispensable source of information. Since the region and road network changed enormously over the last 80 years, it took me some time to explore and compare things but in the end it was possible to pinpoint the correct location thanks to my grandfather’s description.

I arranged for a metal detecting licence and looked up the current owner of that land parcel.

Due to miscommunication and a search ban from the alleged owner, I lost one and a half year before I could finally start my research.

I was aware thay my chances to find large pieces were very small, as the wreckage was being towed away by the landowner at that time. I felt I had never been so happy as then, with the first pieces of wreckage in my hands.

Pieces of shell casings, bullet tips, fuses, a plug from a fuel gauge and other small particles emerged on a small surface and I realised I was in the right place.

In the meantime, I watched many documentaries related to WW2 aircraft and the way they were built.

One day, the company Airframe Assemblies LTD, based on the Isle of Wight, appeared on the television and I decided to contact Steve Visard to ask his opinion on the parts I found.

I was very grateful for his swift response and I was told that the parts belonged to a Hawker Hurricane.

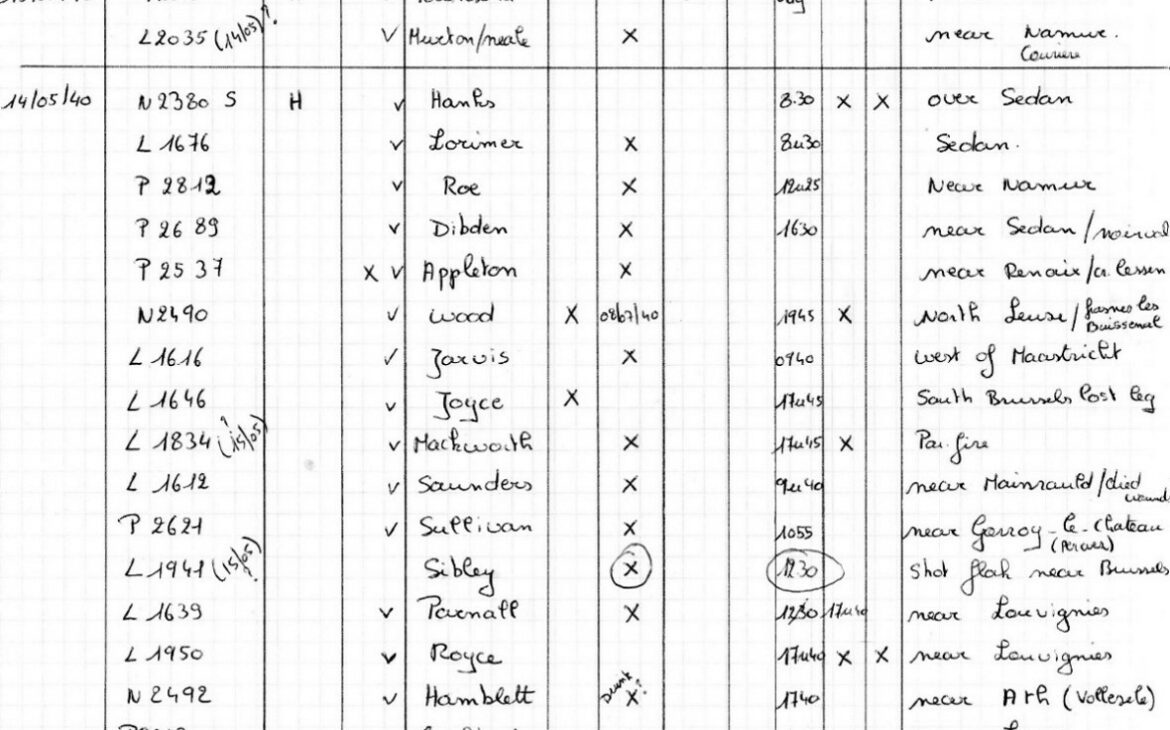

I purchased the book “Royal Air Force, Fighter command losses”, written by Norman L R Franks.

It was the start of the overview I needed.

All the losses in that week for this type of aircraft were listed. With additional online information, the list was completed and every incident was investigated on a case-by-case basis.

In this way, I tried to discover important details of each loss: aircraft number; was the pilot wounded, dead or captured; was the aircraft found, the hour of the crash and the region where all of this happened.

My first presumption headed towards Pilot Officer Appleton and Pilot Officer Sibley.

Both disappeared in the same area on May 14 and were never found.

I decided to learn more about these two persons.

I started with Appleton, since May 14 was marked for him as an indisputable date and for Sibley May 15 was marked in some reports.

The search for Appleton became very difficult. For instance, there were different aircraft registration numbers as well as different locations.

This has connected me with the group Wings Of Memory (https://www.wingsofmemory.be/), a group of passionate enthusiasts who keep the memories of the fallen WW2 crews alive.

I discovered that they already conducted a research on this crash.

I was granted access and it became clear that Appleton’s presumed resting place was outside my search area.

A monument was erected for Appleton at Lessen, the place where it was considered the plane crash happened. However, archaeological research could not offer any certainty on this so far.

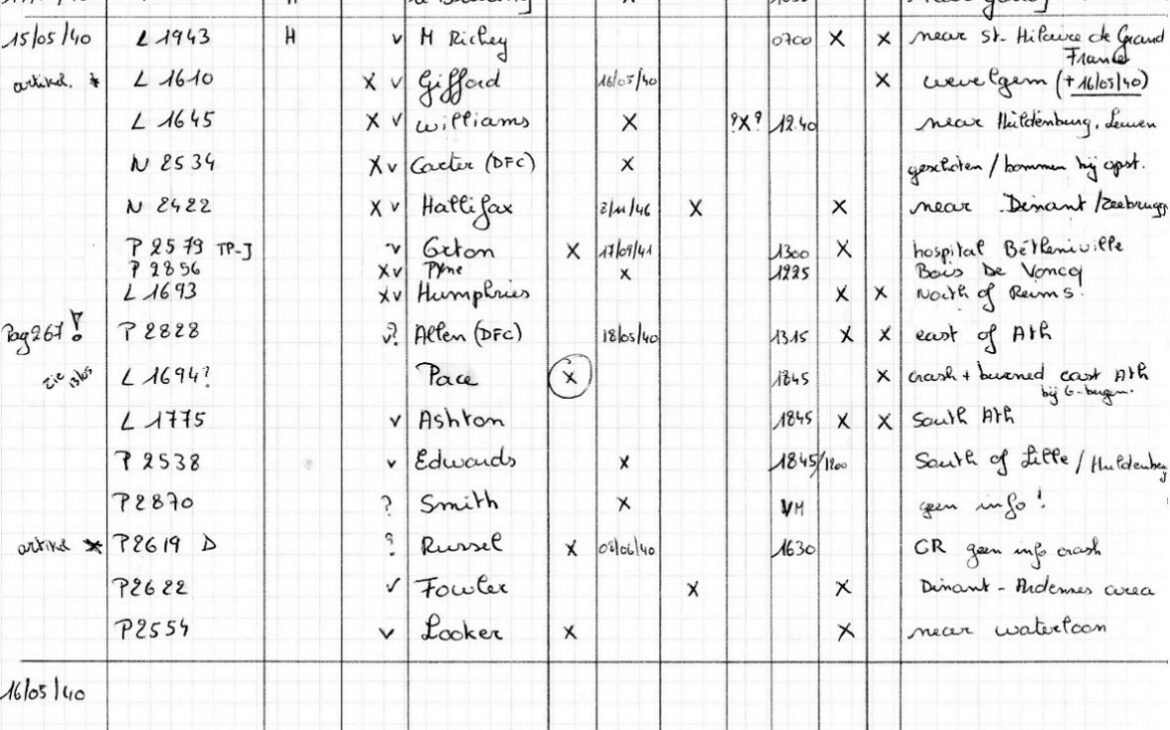

I now decided to focus on Sibley, the other pilot from my list. According to some sources, his plane was hit by anti-aircraft fire over Brussels. I started with my online research and found the number of his personal file, stored at the National Archives in London. This information was only accesible on site so I asked someone to go and copy this on my behalf.

The file consisted of 60 pages and contained more information than I thought. It was hard to read the letters to and from his family. Receiving the message that your son or husband will never come back was the harsh reality.

The several letters his relatives sent to the Red Cross did not bring much clarity.

The question whether he was captured was also posed to the Germans.

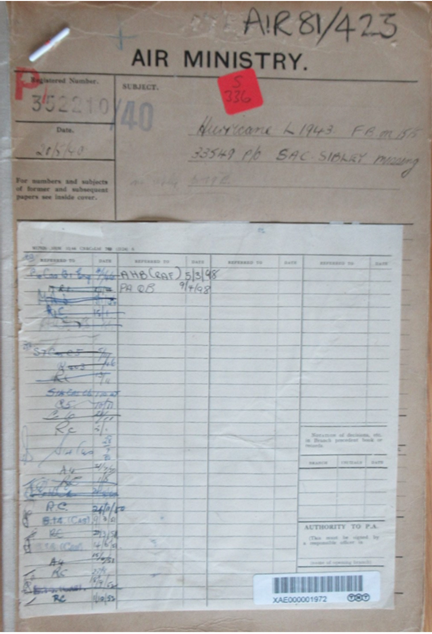

The following document from 1946 proofs how difficult it was to investigate every disappearance.

Pilot Officer Samuel Antony Compton Sibley born March 27, 1920, service number 33549 of 504 SQN would never return.

Thanks to his father in his capacity as Squadron Leader*, his fellow pilots during that day could still be heard.

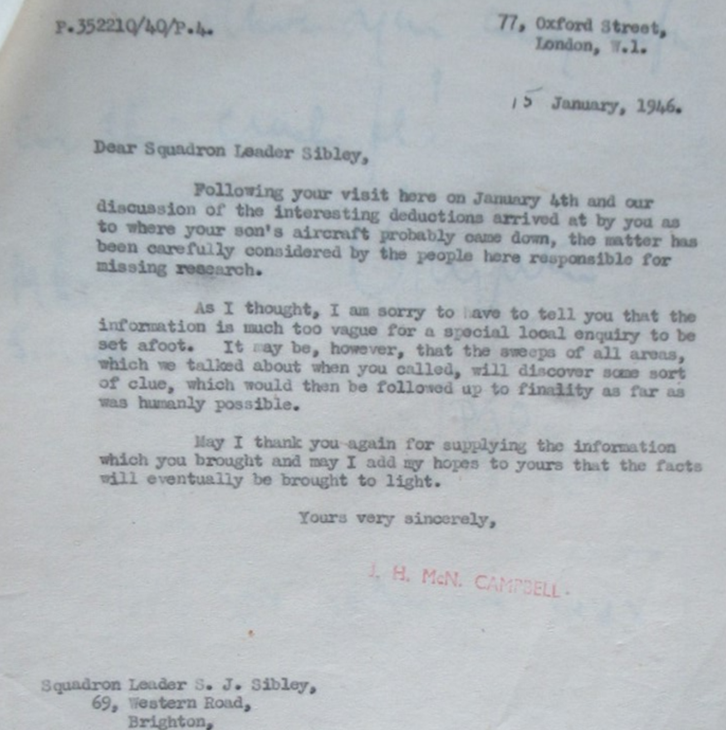

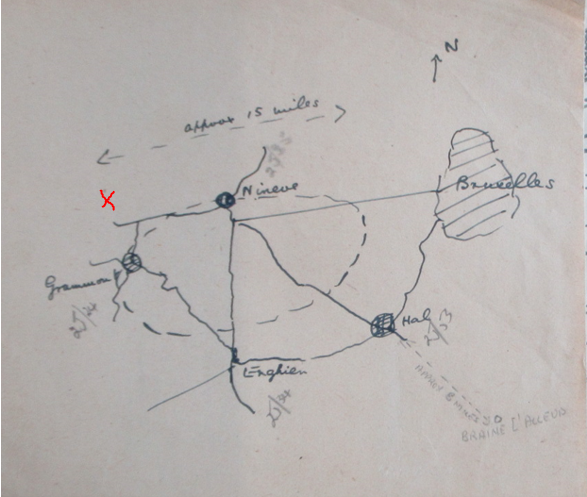

Through their testimony, the file contained the following map.

According to his fellow pilots, he was still fairly in control of the aircraft when leaving the formation.

The map estimated the area where P/O Sibley could have been able to land his aircraft with the damage incurred by anti-aircraft fire.

The distance from Brussels to the crash site is 28km ( 17.5 miles). The plane covered this distance in less than four minutes.

Zottegem and the fields nearby Leenhoutstraat, marked with a red cross, are barely a few seconds flying outside the circle on the map.

*Squadron leaders are the lowest ranking officers allowed to fly a command flag. The flag may be displayed on the officer's aircraft or, if the squadron leader is in command, the flag may be raised from a flagpole or displayed as a car flag on an official vehicle.

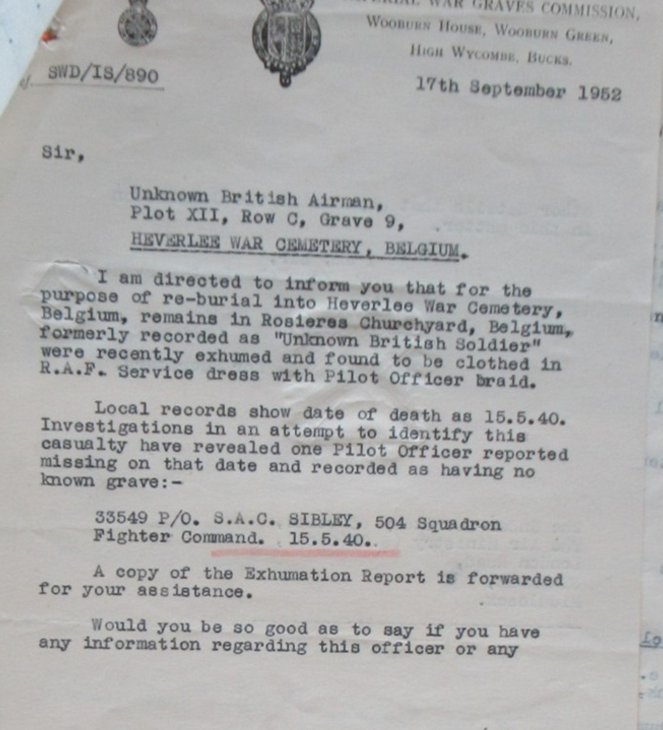

The file also contained the following document, as well as the excavation report of a Pilot Officer at Rosières Cemetery. In 1952, due to certain features that were released during the exhumation, this was considered to be Sibley’s grave. His body was transferred to Heverlee military cemetery and defined as unknown pending further investigation.

Visit to the unknown gravestone at Heverlee military cemetery in summer 2022.

Information received from CWGC (Commonwelth War grave Commission) about some research that took place in the 90s revealed a negative match between Sibley and this grave in Heverlee. The location of his body is up to now still unknown.

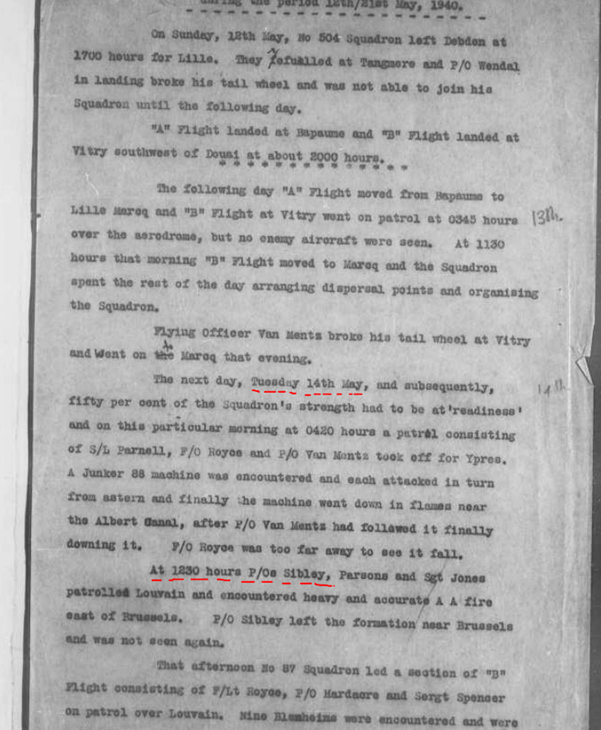

Together with his personal file, I also asked a copy of the Squadron Log (504SQN). This is a list that recorded all flights, flight hours, pilots and aircraft numbers day by day.

Most data between May 11 and May 22, 1940 got lost due to the hasty retreat to Dunkirk during that period.

To my big surprise I discovered a handwritten report at the back of the file. (See the following image).

For me this is the proof that Sibley crashed on May 14 and not on May 15 as stated in some sources.

Unfortunately, further research in local archives, burial registers, neighbourhood surveys, Royal Air Force 504 SQN and hours of detective work didn’t bring new evidence up to now.

As no trace of neither the pilot and aircraft was ever found, P/O Sibley is commemorated on the Runnymede Memorial.

I hereby conclude that Pilot Officer S.A.C Sibley made a reconnaissance flight in the vicinity of Leuven on May 14, 1940. Near Brussels, his aircraft was hit by anti-aircraft fire. He left his formation and tried to bring himself and his aircraft to safety in unoccupied territory back then. According to the official report he managed to land his severely damaged aircraft in the fields nearby Leenhoutstraat in Zottegem around 12.30pm (11.30 am local time).

A few moments after the crash, he was found severely injured by local residents.

After making it clear he was an Englishman, he was transferred to the local hospital where he died of his injuries the day after.

Unfortunately, what happened after his death remains a mystery.

Research conducted by Peter Van de Sijpe, Europaweg 60 – 9620 Zottegem, Belgium

zottegeminoorlog@outlook.com

© Peter VDS